The journey to the West African nation of Cameroon proved to be extremely challenging and an eye-opening experience.

It was the best of trips, it was the worst of trips, it was the most difficult of trips. A journey to the West African nation of Cameroon proved to be extremely challenging and an eye-opening experience, and while Cameroon boasts an impressive herpetological resume, including some of the most iconic reptiles and amphibians known in the herpetological community, few have traveled to this region to explore it for themselves. The reasons for this revealed themselves quite clearly shortly upon my arrival.

This trip took place in 1991 and as part of my continuing research at the time on herpetological parasitology, I hoped to sample some of the amazing diversity found in the southwestern portion of the country. In this region were dozens of frog species, including the goliath frog (Conraua goliath), the world’s largest anuran; the legendary hairy frog (Trichobatrachus robustus) males of which develop hair-like structures over their bodies during the breeding season, enabling them to stay submerged longer in cold streams; as well as numerous colorful reed frogs (Hyperolius spp.), big-eyed frogs (Leptopelis spp.), and even several obscure, subterranean caecilians.

The reptile diversity was equally impressive with nearly a dozen species of chameleons, several hingeback tortoises (Kinixys spp.), bush vipers (Atheris spp.), egg-eating snakes (Dasypeltis spp.), and even the ubiquitous ball python (Python regius) could be found in the area.

Together with my friend and colleague, Joe Furman, we spent a month in Cameroon searching for any herpetological treasures we could find, but in the end, what we found was mostly trouble. The people of Cameroon were not very friendly toward visitors, at least back then, especially those who were observed poking around in their forests and countryside looking for snakes and frogs.

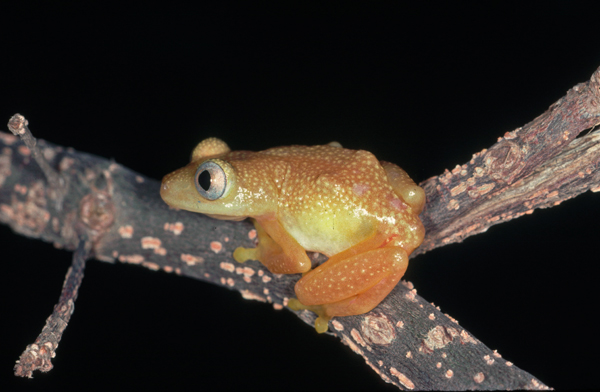

paul freed

The gray-eyed frog (Opisthothylax immaculatus) is an obscure species that the author and his friend were lucky to find.

One of the biggest problems we encountered involved taking photographs. Locals strongly objected to this, and merely having a camera around one’s neck was justifiable cause for them calling the police.

Photographing almost any place, person or thing was justification for arrest. When I was seen photographing the Cameroonian flag, I was promptly arrested and my camera confiscated. I was able to get it back after an exchange of money, but afterward, photography was confined mainly to wildlife in the privacy of our tents.

Speaking of money, Cameroon was the most expensive trip I had undertaken. A can of soda cost $3.50, two eggs in a restaurant were $8, and a gallon of gas exceeded $4.20 (exorbitant, considering this was back in 1991). Joe made a one-minute phone call to the U.S. and it cost him an astounding $30. The piece de resistance came when we rented our vehicle for a whopping $3,000 for three weeks, plus an additional 45 cents per mile! This, plus all the fines we had to pay to stay out of jail, completely bankrupted us.

From Bugs to Bufonidae

Situated just north of the equator, the temperatures in the southwestern region of Cameroon are extremely high. Combined with humidity approaching 100 percent, field conditions at times were difficult at best. We eventually found some forested habitat with minimal human impact and set up our campsite close to a stream several miles from the city of Loum.

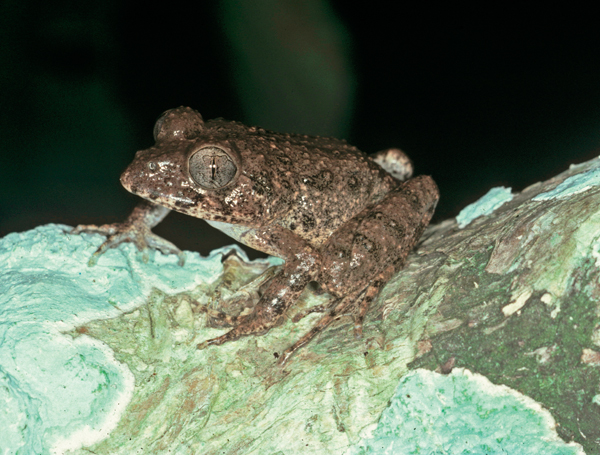

paul freed

A Gaboon forest frog (Scotobleps gabonicus) found at night near Loum.

Mosquitoes are naturally to be expected, especially near water sources, but we were not prepared for the onslaught we experienced as the sun set. Thick clouds of the insects descended upon us despite the liberal application of strong repellent. These terrors were replaced during daylight hours by an even more insidious tormentor: sweat bees. Although not a true bee, they don’t sting, but they do bite. Thousands of these tiny bugs would try to attach themselves to any exposed body part and their painful bites would produce angry, red welts that burned and itched for days. And then there were the ubiquitous biting ants that found us day and night wherever we went.

As darkness approached, we could hear the calls of several frogs near the water. Our flashlight beams eventually found the callers, and we were delighted to find several representatives of the Arthroleptidae (bush squeakers) and the Hyperoliidae (reed frogs), including the West African screeching frog (Arthroleptis poecilonotus), variable squeaker frog (A. variabilis), modest forest tree frog (L. modestus, in amplexus), Cameroon forest tree frog (L. brevirostris) and the Gaboon forest frog (Scotobleps gabonicus), among others.

PAUL FREED

This banded gecko (Hemidactylus eniangii) was revealed beneath the loose bark of a rotting log.

Toads (Bufonidae) are represented by two dozen species in Cameroon and we were happy to find two of the smaller representatives: the African tree toad (Nectophryne afra) and Bate’s tree toad (N. batesii). These species are actually arboreal and feed primarily on ants, and we enjoyed watching a Bate’s tree toad as it sat on leaves about 4 feet off the ground, eating a steady column of ants that was passing near it.

The find of the day, however, were several goliath frogs that emerged at night by the water’s edge. Although not at all colorful or possessing any flamboyant ornamentation, these elusive giants had gained an almost mythical status among amphibian enthusiasts. Large adults can exceed 12 inches in length, and with legs extended they can easily double that size. Goliath frog s are extremely alert and nervous, and do very poorly under captive conditions. It was for those reasons, as well as the request of Cameroon’s leading amphibian authority, Dr. Jean Louis Amiet, that I opted not to collect any, but rather just enjoyed observing them. Sadly, one of the major contributing factors to their decline in the wild is their consumption by the local people.

A White-bellied Pangolin (Manis tricuspis)

The next morning we found a number of rotten logs in the forest and beneath the bark of one we found a juvenile banded gecko (Hemidactylus eniangii). As we photographed the lizard, we heard a soft rustling nearby that turned out to be a Home’s hingeback tortoise (Kinixys homeana) grazing on the forest floor. As we stood marveling at it, a man emerged from deep in the woods carrying a torn plastic bag with what looked like a small armadillo inside.

paul freed

The author and his friend purchased this white-bellied pangolin (Manis tricuspis) from a local man in order to save it from possibly becoming the man’s dinner. They released it a short time later, in secret.

He spoke to us in his native language and from what we understood he wanted to sell us the animal. He dumped it from the bag onto the ground, and we immediately recognized the animal as a young white-bellied pangolin (Manis tricuspis)! Joe and I stood there staring in awe at the magnificent mammal that began to slowly uncurl from its balled-up defensive posture to survey its surroundings. We really had no reason to buy it, but we knew that if we didn’t this poor creature would likely end up in the man’s dinner pot. So we gave him some money and later released the pangolin away from prying eyes.

paul freed

The author found this Fischer’s cat snake (Toxicodryas pulverulenta) under his tent one morning.

With our campsite discovered, we decided to search for another place to use as our home base. As I began packing up my things, I noticed a subtle lump moving slowly beneath the floor of my tent. I lifted the tent up and was surprised to see a snake hastily making its way to a nearby tree. It was a Fischer’s cat snake (Toxicodryas pulverulenta) that had likely crawled under my tent during the night.

Given the extremely high temperatures of the area and the discomfort they caused, Joe and I decided to look for cooler accommodations at a higher elevation, traveling southwest toward the Buea area near Mount Cameroon. Along the roads we traveled I had my first brush with the phenomenon known as “bush meat.”

Men would stand by the roadside displaying dead exotic animals that were illegally poached from the surrounding forests. I saw endangered primates, such as the red-capped mangaby (Cercocebus torquatus) various species of guenon (Cercopithecus spp.), cane rats, porcupines, deer and even monitor lizards. These are only a few of the recognizable species I could identify as we made our way through the remote countryside. Bush meat animals are sold as food and are generally preferred by locals over domestic beef and fowl. The practice is not unique to Cameroon or even Africa—it occurs in many other regions of the world—but this was the first time I witnessed these disturbing sights and they added greatly to the overall psychological hardship of the trip.

A Cameroon Water Frog

By early evening we were passing through the village of Mutengene (pronounced Moo-ten-ha-nee) when we crossed a small bridge over a stream. Joe heard a frog calling from the water’s edge, so we parked our vehicle on the side of the road and made our way down to the water.

paul freed

A male crested chameleon (Trioceros cristatus) that was also found at habitat lower in elevation, near Buea.

Large boulders lined the stream and as it was getting dark, it was difficult navigating the slippery rocks. Ultimately, we found the source of the call: an obscure Cameroon water frog (Petropedetes cameronensis) from an even more obscure family, the Petropedetidae, which is represented by only a dozen species. We immediately began photographing the frog, which sat motionless on top of a large, flat rock. As our flash units bombarded the hapless amphibian again and again, I noticed a large group of people had gathered around our vehicle up on the bridge.

I suggested to Joe that we leave, but by the time we made it up to our car, the mob had grown considerably and for some reason they were very angry and extremely vocal. We were quickly surrounded, and several young men held on to us, shouting that we would be taken to the village chief who would determine our fate.

Naturally, we were shocked and frightened by this turn of events, as we really didn’t think that photographing frogs was considered so taboo in Cameroon. We soon learned that the local people thought that the flash bursts coming from our cameras were caused by us detonating bombs! After being brought before the village chief, we were relieved that the elderly man in charge quickly realized that we were not terrorists and demanded that we be released immediately.

Joe and I were quite shaken by this experience, and we later found out that the entire scene could have played out much worse. We learned that most of the local people don’t have much faith in the police as they are prone to bribery, and we heard stories of murderers who were set free by the police after receiving even modest monetary bribes.

Arriving near the foothills of Mount Cameroon was exactly what we needed to shake off the horrors of recent events. The temperatures were much cooler, the crowds of people were greatly diminished, and we were hoping that the herpetofauna would be even more abundant and diverse than we had previously been finding. Soon after checking into our accommodations we began searching the surrounding forests for amphibians and reptiles.

After hiking for several hours, we came upon a group of youngsters playing in a clearing, and they immediately approached and asked what we were doing there. After we explained that we were looking for reptiles, one of the boys pointed into a tree and asked, “You mean like that one?” We swiveled around to see that he was pointing to the top of a tree about 40 feet away, where a chameleon was perched on a thin branch.

“Yes, exactly!” was my response, but how would we get to the chameleon? There was no way Joe or I could possibly climb the fragile, delicate tree high enough to reach it. Without hesitation, two of the boys began breaking off long, thin branches. One of them used his to gently prod the chameleon while the other placed his branch directly in front of it. Within seconds, the chameleon walked onto the waiting branch and the young man lowered it down to my waiting hands. It was so simplistic and amazing to watch, and there in my grasp was a beautiful male Cameroon sailfin chameleon (Trioceros montium)! We thanked the boys with some treats we had with us and continued on our way to search for more treasures.

paul freed

A Bate’s tree toad (Nectophryne batesii) dines upon a trail of ants.

Hours later, we had several pairs of sailfin chameleons as well as a number of crested chameleons (Trioceros cristatus). Yet despite the relief of cooler temperatures and finding the two species of chameleons, as well as several common skinks (Trachylepis affinis), we decided that the herping would be better down at the lower elevations where the warmer, more humid forest would have a greater diversity of herpetofauna.

We descended to the city of Limbe, located on the extreme southwestern coast of Cameroon, where we stopped at the local zoo. It featured only a few monkeys, several birds and two reptiles, but one of the staff advised us to visit a forest near the village of Mbalangi to search for snakes. His advice paid off, and with his help we soon found a beautiful African burrowing python (Calabaria reinhardtii) and a feisty spotted night adder (Causus maculatus).

Beneath the leaf-litter on the forest floor we uncovered an exceptional spiny toad (Amietophrynus tuberosus), as well as a slender forest gecko (Hemidactylus ansorgii). The low vegetation yielded some interesting frogs, too, and as darkness fell we found a nice diversity of reed frogs, including the rare gray-eyed frog (Opisthothylax immaculatus), the variable reed frog (Hyperolius concolor) and an attractive Victoria Forest tree frog (Leptopelis boulengeri).

Leaving Cameroon in Frustration

After a month, and under less than ideal circumstances, it was eventually time to leave Cameroon. But before we could depart, we had to make one more trip to the permit office to obtain export permits for the specimens we had collected. In Cameroon, however, even this normally straightforward task turned out to be riddled with problems.

paul freed

This beautiful African burrowing python (Calabaria reinhardtii) was found with the help of a local man who recommended a good place to find snakes.

To begin with, I had to pay a fee for each specimen collected, ranging from 2 dollars for small frogs and lizards to 20 dollars for turtles and snakes. I tried explaining to the administrator that I was collecting under a scientific permit and not a commercial one and was told that these were the fees for a scientific permit; those for a commercial permit would be substantially higher.

At this point all our money was gone, but that wasn’t even the worst of it. Upon examining the finished export permit, I noticed that any amphibian or reptile of which we collected more than one species was lumped together into a single name. So the two species of chameleons were listed as Chamaeleo, all the toads were Bufo (at the time these animals were collected, they were still in the genera Chamaeleo and Bufo; now they are considered Trioceros and Amietophrynus), and so on. I tried explaining that this would result in problems upon my return to the U.S., but the administrator said that was not his concern.

paul freed

These modest forest tree frogs (Leptopelis modestus) were found engaged in amplexus.

Sure enough, upon landing back in the States, I declared my specimens to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, whereupon all the specimens we collected were confiscated due to incomplete and inaccurate permits. Such was a fitting end to an incredibly difficult trip.

After several months of lengthy communications with the USFWS I was finally able to convince them that all the specimens were collected and exported legally, and they were ultimately returned to me. Unfortunately, more than half of them had died during this process.

This memorable trip took place nearly a quarter century ago, and while Joe and I experienced numerous problems and setbacks, it is hoped that conditions today have since improved in Cameroon, and that visitors may now have a much better overall experience. The herpetofauna is admittedly amazing, so good luck if you go!

Paul Freed is the former supervisor of herpetology at the Houston Zoo. He retired after a 25-year career and moved to the Pacific Northwest, where he and his wife Barbara continue to travel domestically and abroad to enjoy the great outdoors. He now spends much of his time photographing amphibians and reptiles as well as writing about his travel adventures. His book, Of Golden Toads & Serpents’ Roads, chronicles Paul’s passion for travel and the allure of observing reptiles and amphibians in the wild.