Proven tips for keeping and successfully breeding the Java hump-headed lizard.

Anyone who sees a Java hump-headed lizard (Gonocephalus chamaeleontinus) also known as the chameleon forest dragon or chameleon anglehead lizard, would agree that it is an aesthetically captivating creature. This elusive lizard, also commonly referred to as a chameleon forest dragon or anglehead lizard, is native to Java, Sumatra and Pulau Tioman, an island off the east coast of peninsular Malaysia. Reaching lengths of close to 12 inches, this agamid dwells mostly in trees and shrubs in humid rain forests. It can even live at altitudes of 5,000 feet.

Stephen Howard

The Java hump-headed lizard relies solely on camouflage as its means of defense, and it has the ability to change the color of its skin from bright green to dark brown within a matter of seconds.

The Java hump-headed lizard relies solely on camouflage as its means of defense, and it has the ability to change the color of its skin from bright green to dark brown within a matter of seconds (hence the other common name of “chameleon”). Typically active during the day, G. chamaeleontinus is found close to water sources such as freshwater streams.

This lizard provides a perfect example of sexual dimorphism in reptiles. Adult males are typically brightly colored with shades varying from forest to mint green. They are also distinctly ornate, with brightly contrasting yellow splotches and a large, spiky nuchal crest directly behind the head. While females also have a nuchal crest, the males’ are more pronounced.

Male hump-headed lizards are incredibly territorial and will display to ward off encroaching competitors. During such displays, a male will extend its large dewlap, arch its back, extend its legs, and open its eyes very widely. The skin may also exhibit a vast array of contrasting green, yellow and brown coloration. It is rare for a physical confrontation to follow suit as disputes are usually resolved by competing displays only.

A similar display by males is sometimes used during courtship, just prior to attempted copulation, with the added physical motion of rapid head twitching. Normally, males will reach a maximum weight of around 120 grams. Females are smaller, usually reaching a maximum weight of 100 grams. Females tend to be brown in appearance, possibly to aid in camouflage while laying eggs. Gonocephalus chamaeleontinus also has bright blue pigment at the corners of its eyes, adding to this lizard’s already fantastic appearance.

Hump-Headed Lizard Husbandry

Although this interesting-looking lizard may be relatively inexpensive, it is not recommended for beginner reptile enthusiasts. Hump-headed lizards do not drink from standing water sources in the wild—they drink droplets off leaves and bark—and because they require constant high humidity, finding an appropriate means to supply water can be difficult for a beginner.

stephen knoop

This setup is ideal for humidity dependent species such as the Java hump-headed lizard.

Drops of water running down the side of their enclosure, or collected on foliage inside it, will entice hump-headed lizards to drink. Usually, water droplets must be somewhat large to illicit a drinking response. While fogging systems aid in maintaining high humidity, they simply do not provide the larger drops of water these lizards seem to like.

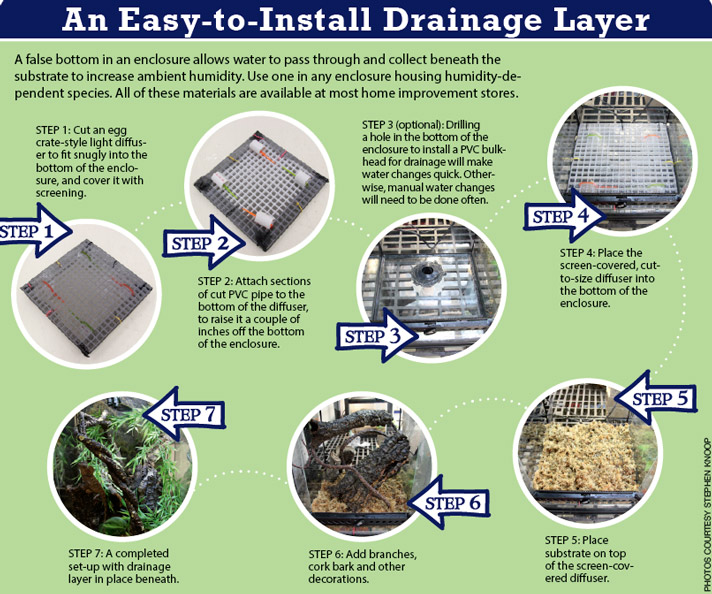

Maintaining high humidity is essential to successful captive management for this species, and at the Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center, where I worked with G. chamaeleontinus, we found the best way to approach the hydration conundrum is to install automated misting systems. We created false bottoms for the lizards’ enclosures, as well.

A glass enclosure is also recommended. It is much easier to retain humidity inside a glass enclosure as opposed to a screened one. Screened enclosures do not trap enough humidity, plus they are sometimes made of metal screening which can rust. The lizards’ claws might also get stuck in metal screening, which can lead to serious injury.

Obviously not everyone has access to automated misting and draining supplies. Hand plant misters, available in any gardening department, are fine, too. If using a hand mister, be sure to mist your lizards’ enclosure liberally three to four times a day.

The hump-headed lizard is arboreal and diurnal, and individuals are exposed to ample amounts of sunlight in the wild. To emulate this need for sunlight in captivity, high-output light fixtures are recommended, equipped with high-output UVB bulbs. Equipping the enclosure with high-output UV bulbs will encourage the lizards’ natural synthesis of vitamin D and calcium absorption, which is extremely important, particularly with juveniles. In addition, a basking light should also be provided. Under-tank heating will not work, as hump-headed lizards spend most of their time basking atop branches and greenery, not on the bottom of their enclosures.

Stephen Howard

A few hump-heads can be kept together in one enclosure, but not adult males because they will engage in territory disputes.

Because these lizards are arboreal, their enclosures should be taller than they are wide, to create a vertical temperature gradient so the hump-headed lizards can properly thermoregulate throughout the day. Basking spots should hover around 95 degrees Fahrenheit, while ambient temperature inside the enclosure should be 75 to 80 degrees. The basking spots will aid the lizards in digestion.

Enclosure decoration and outfitting also needs to be taken into consideration when trying to replicate any reptile’s native environment. Being that G. chamaeleontinus is arboreal, an ample amount of climbable branches is necessary to ensure the well-being of this lizard. Flexible wire vines (often available in stores that sell reptile supplies) are ideal for hump-headed lizards of all sizes and ages; adults also do quite well with sections of cork bark. Be sure that any cork bark you purchase has been properly treated. It can also be “baked” at 200 300 degrees in a conventional oven for several hours, to kill any residual fungal spores.

Regardless of what types of tree-emulating decorations are used in a hump-headed enclosure, some of the branches need to be placed under the heating and lighting fixtures so lizards may bask efficiently. A high humidity-promoting substrate should also be used, such as a thick layer of sphagnum moss, which in our experience seems to work best. Sphagnum moss should be thoroughly rinsed in water prior to use, though, as it can sometimes contain high amounts of salt.

When setting up enclosures for hump-headed lizards, keep in mind that males should never be housed together due to their territorial nature. Although it is rare for males to resort to physical altercations, a dominated male subordinate will be under constant stress and not flourish in captivity. Males can be housed with several females, the number of which depends on the size of the enclosure. It is recommended to keep single adults in an enclosure with dimensions no smaller than 18 inches long, 18 inches deep, and 24 inches tall. We have successfully kept groups of four hump-headed lizards in enclosures measuring 24 inches long, 24 inches deep and 48 inches tall.

What to Feed the Java Hump-Headed Lizard

Gonocephalus chamaeleontinus is an invertebrate ambush predator, relying on a diet of slugs, worms and some insects in the wild. In captivity, it will accept night crawlers, waxworms, mealworms and crickets.

Stephen Howard

Adult hump-headed lizards thrive on a diet of whole night crawlers and large crickets.

Strangely, hump-headed lizards seem to be attracted to food items that seem much bigger than they are capable of eating, and will sometimes completely ignore a food item that is too small. Hatchlings emerge weighing less than 2 grams each, so we offered them a variety of small food items such as fruit flies, pinhead crickets and small mealworms. However, we found that within a couple weeks, they prefer to eat nearly adult-sized mealworms and small waxworms. Hatchlings should be offered food every day without fail. Once they grow a little larger, the decision can be made whether or not to offer “red-wiggler” worms (Eisenia fetida).

Some articles have warned against feeding red-wigglers to certain species of reptiles, as in some cases, red-wigglers have been lethally toxic when used as a food item. Commercially available red-wigglers, which are normally used to aid in composting, are often multiple species that are sold in a batch and referred to collectively as “red-wigglers.” We fed them to juvenile hump-headed lizards that were not big enough to eat night crawlers, and never had an issue with toxicity, but after reading several articles on the topic, we decreased offering them as a precaution. The lizards did seem to really enjoy them, and the worms certainly live up to their “wiggler” name, but the choice as to whether or not to offer them lies with the keeper.

Adult hump-headed lizards thrive on a diet of whole night crawlers and large crickets. Offer food to adults every other day, alternating prey items with each feeding. When offering whole night crawlers, you may think that it is physically impossible for your hump-head to eat the worm in its entirety. The truth is, hump-headed lizards can eat up to four whole night crawlers with ease, ingesting them in a matter of seconds. The worms can be offered to the lizards by hand, tweezers or tongs, or they can be pinned to a piece of cork bark for later consumption (in which case, be sure pins are secured firmly, as the lizards may tear at a pinned worm with vigor, and could potentially dislodge a pin that isn’t attached properly).

Nutritional supplementation is extremely vital to the successful captive management of the hump-headed lizard. Many reptiles are susceptible to metabolic bone disease, and the hump-headed lizard is no exception. Hatchlings are at high risk of hypocalcemia, a metabolic bone disease associated with low amounts of calcium. Vitamin D³ is necessary to promote proper calcium absorption, and without it, hypocalcemia can become a major problem. In addition to the high-output UV bulbs that will encourage natural synthesis of vitamin D³, supplements that include vitamin D³ and calcium should be used with every feeding. We provide Repashy’s Calcium Plus supplement with every feeding, as it has an appropriate vitamin D³-to-calcium ratio, in addition to other essential vitamins and minerals.

Reproduction Strategy for Java Hump-Headed Lizards

Despite the presence of G. chamaeleontinus in the pet trade, there have been few instances of successful reproduction of the species in captivity. A handful of hobbyists have accomplished the task, as well as a small number of zoos and aquariums. The Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center has had multiple breeding successes over the past two years. By communicating with other facilities and hobbyists, reproduction of the hump-headed lizard has been refined to an art.

Stephen Howard

Young hump-heads should be separated according to size as they grow older, to prevent food competition.

Females should weigh more than 60 grams before being introduced to a male. They can ovulate prior to achieving this weight, but if they weigh less and become gravid, there is an increased risk of egg binding. Also, when introducing two lizards of the opposite sex, if they are kept separately, it is generally better to introduce the female into the male’s enclosure. This way, the male is less distracted and stressed by being transported to a new enclosure, and can focus on the female.

At the Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center, we had the most success when male and female hump-headed lizards were housed together for an extended period of time. A male will usually puff out his dewlap and stand tall to display for the female. Similar to the territorial display, he will also twitch up and down while displaying. After a few moments of showing off to the female, he will run to her and bite onto her nuchal crest. This serves as an “anti-bucking” anchor, keeping the male mounted while he twists his tail under the female’s to insert his hemipenes. A coupling can last up to 10 minutes, but is usually shorter.

After six to eight weeks of gestation, a female’s abdomen will begin to swell. Eggs can be gently palpated through the skin. Eventually, the female will dig a nesting hole, which can be as deep as 6 inches. For this reason, it is important to keep the substrate fairly loose and easy for her to dig through.

Inside the hole, a healthy female will lay four to 13 oval eggs, each measuring about an inch in length. Interestingly, she will then use her face to push substrate over the eggs. Females doing so may even be observed hitting their faces, somewhat violently, against the substrate to pack it down over their eggs.

Normally, a female will lay eggs once or twice a year. The eggs should be artificially incubated for the best chance of successful hatching. A vermiculite incubation substrate, slightly dampened, has proven successful for us. After experimenting with a few different incubation methods, we have had the best results incubating at 77 to 78 degrees with a relative humidity of 87 percent. Under these parameters, incubation should last 70 to 90 days, with most eggs hatching around day 80. If an egg does not hatch on its own, it is possible to assist a hatchling lizard by carefully cutting the egg open. However, in my experience, individuals that need to be assisted with hatching have a much lower survival rate over the long run.

Hatchlings are entirely precocial, needing no help from their parents. An entire clutch of hatchlings can normally be housed together, but should be separated according to size as they grow older to prevent food competition.

The Need to Breed

As mentioned, although hump-headed lizards can be found in the pet reptile trade, there are only a few hobbyists who are trying to breed this species. A typical adult hump-head might sell for an average price of $100, and because they’re relatively inexpensive, major breeders are mostly unwilling to spend the time and effort to breed this species in captivity. The lizards are, however, regularly imported from Indonesia, and it is easy to tell when a fresh shipment has arrived because multiple listings from different vendors will be posted online almost simultaneously. Be sure to quarantine any hump-headed lizard you receive, as it has probably just arrived from the wild.

stephen howard

Young and mature Java hump-headed lizards.

As of this writing (January 2015), the IUCN Redlist has not evaluated the conservation status of G. chamaeleontinus, and as such, it is unknown what effect the pet trade may be having on wild populations. It will be up to individuals with a passion for these beautiful lizards to successfully keep and breed them. Breeding the hump-headed lizard in captivity will not only fill in the gaps of information we have yet to discover about this elusive animal, but will lead to an established, sustainable population.

Currently there are fewer than 40 specimens of G. chamaeleontinus in zoological institutions throughout the U.S.—40 individuals total. There are many more in private collections, and it is my dream that zoological institutions and hobbyists will work in unison to establish sustainable propagation techniques. The Java hump-headed lizard is a beautiful, ornate species that deserves our respect and efforts to conserve its current population in the wild.

Stephen Howard has been interested in reptiles from an early age. He has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Virginia Tech, previously worked as a herpetologist at the Virginia Aquarium and Marine Science Center, and currently works in the herpetology department at the Dallas Zoo.