Neurergus kaiserii was once listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, but more recently its classification was changed to Vulnerable.

The beautifully colored, orange, black and white Kaiser’s mountain newt (Neurergus kaiseri), also known as the Kaiser’s spotted newt, Luristan newt and emperor’s spotted newt, would be a gem in any collection. It is rarely encountered in the pet trade, however, and N. kaiseri is a rare species in the wild, too. Sadly, this newt of many names is currently listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

emma lawlor

Adult Kaiser’s mountain newts at Sparsholt College. A female is on the left; male on the right.

Kaiser’s mountain newt has been the subject of multiple captive-breeding programs. One that has been successful is underway at Sparsholt College in Hampshire, England, and this article will describe the methods used at Sparsholt to breed and rear this beautiful and endangered animal.

Kaiser’s Mountain Newt Natural History

Kaiser’s mountain newt may be found in areas up to about 4,921 feet above sea level in the Zagros Mountains of Iran. The species, like most newts, is closely associated with water and wild specimens are not believed to stray far from their water sources. Generally, N. kaiseri is most likely to be found in open patches of oak woodland near streams, though individuals have also been found in other habitats and water sources, including ponds and pools, man-made water reservoirs, and even on the edges of waterfalls.

bill love

Neurergus kaiserii was once listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, but more recently its classification was changed to Vulnerable.

Most Neurergus species are found only in running water, but the Kaiser’s spotted newt seems able to utilize a wider range of water types. Some individuals have even been found in water troughs used with cattle. During spring floods, newts that inhabit running water may be flushed down waterfalls and into new habitats.

For several months each year, the Zagros experience a dry season, when Kaiser’s mountain newts must undergo aestivation in order to survive. At this time, newts may be found inactive under rocks, pebbles and logs.

In the wild, Kaiser’s mountain newts feed on a range of invertebrates, both on land and in water. As an insectivorous species, it takes well to a range of different prey items when offered in captivity.

It was in 2006 that the IUCN Red List described N. kaiseri as Critically Endangered, the highest category of extinction risk for species that are not already classified as Extinct or Extinct in the Wild. The challenges facing the animal in the wild are manifold, and one of the greatest is collection by humans. As an attractive newt, there has historically been much interest in collection of this species for the pet trade, and the level of harvest may be unsustainable, meaning the wild population cannot replenish itself quickly enough to survive.

emma lawlor

One of the female newts at Sparsholt College, swollen with eggs.

The Kaiser’s mountain newt is a species that relies heavily on water sources. In dry environments, individuals may rapidly dry out, and it is believed that climate change and localized drought in the newt’s habitat may be contributing to the wild population’s decline. In addition, diversion of water for agriculture and for watering of cattle may be reducing the availability of rivers and streams.

Yet another threat is invasive fish (Barbus spp.) of the family Cyprinidae that are now found in many of the bodies of water that Kaiser’s mountain newts inhabit. It is believed that these fish may be eating adult newts and offspring.

While the species’ situation in the wild is a very depressing one, the Kaiser’s mountain newt isn’t totally doomed. Recent surveys by the IUCN found more surviving wild newts than had initially been believed. The Kaiser’s mountain newt, it seems, might be doing better in the wild than first thought, and it has been downlisted to Vulnerable. Further conservation work and research is required to protect the wild population of Kaiser’s mountain newt. Sparsholt College’s Animal Management Centre had great success in breeding the species, and what follows is our recipe for success in breeding this amazing amphibian.

Kaiser’s Mountain Newt Brumation

As a species from a temperate zone, Kaiser’s mountain newts require a cooling or brumation period in order to be bred successfully. Following a year in a terrestrial set up with temperature ranges from 68 to 78 degrees Fahrenheit, and a UV index of 1.5 to 2, the brumation cycle began on November 25, 2016. Two adult male newts and two adult females were each placed into a small, plastic tub measuring 10 by 15 inches, separating the genders. Each tub was packed with a 1-inch layer of loose, damp, sphagnum moss, and a small water dish was provided to maintain hydration.

emma lawlor

Some of the beautiful Kaiser’s mountain newts that currently reside at Sparsholt College.

For the first week of brumation, the newts were conditioned to slightly lower temperatures of 64 to 68 degrees. During this time, ultraviolet light provision was removed, thus mimicking the natural conditions of a cool, dry environment. Furthermore, feeding was totally halted.

The next step of brumation involved a refrigerator. Both tubs of newts were placed in a specialist fridge with the temperature set to 50 degrees. The water dishes were also removed from both tubs to avoid cooling the newts excessively.

During the ensuing — and admittedly nerve-wracking — brumation period, the temperatures within each tub were checked daily, as well as the dampness of the moss and the body condition of the newts. Over the entire two-month period, the temperatures varied only marginally, ranging between 46 and 50 degrees.

Kaiser’s Mountain Newt Post Brumation

Following brumation, the newts in their tubs were removed from the refrigeration unit and given a week to warm up and feed on second instar banded crickets at temperatures of 64 to 68 degrees. The water dishes were also placed back into each tub for rehydration.

During this period, a glass aquarium measuring 2 by 1 by 11/2 feet was set up with mature water (water that had been aged in order to dechlorinate it). It contained a rock pile that breached the water’s surface and islands of floating cork bark. In addition, both live and artificial plants were provided, either floating or submerged to half the depth of the water. To simulate natural sunlight, a 2 percent T8 18-inch UV light tube was placed over the tank, providing an index of 1.5 at the top of the rock pile. Water temperature was maintained at roughly 72 degrees.

After one-week conditioning post-brumation, the newts were removed from their tubs and placed in the aquarium together at the same time. Immediately, hiding behaviors were observed, with the newts making use of the gaps in the rock pile. After giving them a day to settle in, earthworms were offered and readily consumed.

On the second day and throughout the first week, the initial signs of breeding behavior were observed, with the males vigorously waving their tails. Water changes replacing approximately 5 to 10 percent of the water with mature water were performed daily. Food was offered two to three times a week and consisted of bloodworms and earthworms.

Over the next couple of weeks, the females’ abdomens swelled noticeably, as did the cloaca and caudal hedonic glands of the males.

Kaiser’s Mountain Newt Eggs

The first Kaiser’s mountain newt eggs were laid on February 17, 2017, two weeks after the adults were placed into their aquatic enclosure. Initially, one or two eggs appeared sporadically around the tank. These were often deposited among both the artificial and live plants. After a few days, many of these eggs detached from the plants and settled on the bare floor of the tank.

emma lawlor

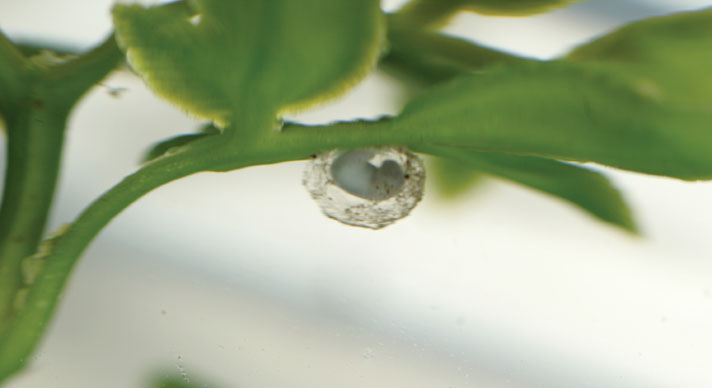

Egg and larvae development, Day 2.

If an egg was fertile, the embryo began to change into a characteristic “C” shape within a couple of days. Infertile eggs, by contrast, tended to turn a gray color, and no change was observed within the center of these eggs. A mix of eggs — both fertile and infertile — were scattered in this fashion throughout the enclosure.

JAMES BRERETON

Egg and larvae development, Day 5.

Then, on March 5, the two female newts were observed adhering eggs securely to the foliage, and the number of eggs laid at one time changed from just a few to dozens over the next several days. The eggs were photographed and observed throughout their development, and gestation from laying to hatching was on average about nine days.

emma lawlor

Egg and larvae development, Day 7.

Caring For Kaiser’s Mountain Newt Offspring

A nursery tank measuring 24 by 18 by 18 inches was set up with décor consisting of thin, slanted rock, live aquatic plants and cork bark. The water depth was 4 inches and heated to 71.6 degrees using a thermostatically controlled water heater. The water was also aerated using a double-outlet air pump. While the tadpoles remain aquatic, they require the water to be rich in oxygen, and until their lungs have fully developed they continue to require oxygenated water for respiration.

emma lawlor

The front legs can be seen on this developing larva.

Both larvae and mature eggs were placed in the nursery tank. Water changes were performed daily with the removal of 10 percent of the water and refilled with mature, dechlorinated water.

Fresh daphnia were offered on a daily basis to all hatchlings. As the larvae began to grow, bloodworms were offered as a supplement; these provided larger, more calorie-rich food items to support the tadpoles’ rapid growth phase.

Kaiser’s Mountain Newt Metamorphosis

After three months, the tadpoles were beginning to emerge, having metamorphosed into tiny newts. While not every egg had hatched and not every tadpole reached the metamorph stage, the survival rate for those reaching metamorphosis was significantly improved. As of this writing, all metamorphosed individuals have survived so far!

Room temperature was maintained relatively warm, at roughly 72 degrees. Once the newts had fully grown their arms and legs, they were moved from the nursery tank into growth tubs, measuring 111/2 by 6 by 4 inches. These were modified to provide additional ventilation through the inclusion of drilled holes and contained several pieces of cork bark for hiding and damp tissue paper as a substrate. The tubs were sprayed on a daily basis to maintain humidity between 60 and 80 percent, and each young newt was fed on a diet of fruit flies and first instar banded crickets. The newts were maintained in groups of six to eight for rearing.

So Where Are We Now?

As of this writing, we’ve successfully metamorphosed a large group of more than a dozen Kaiser’s mountain newts, with several more yet to undergo metamorphosis. Currently, the newts are still in their growth tubs, where they are being fed on a diet of small invertebrates such as first instar crickets and fruit flies. In time, we plan to introduce the youngsters into a large show tank, where they may be observed by visitors and students. Given our level of success, we also plan to send some of the newts to other zoological institutions so that breeding and populations may continue to grow.

The Kaiser’s mountain newt is a stunning amphibian with a fascinating conservation success story to tell. With attention to detail, it is clear that these newts can be bred quite successfully within a captive collection. With brumation and a carefully planned diet for the offspring, the newts respond well to captivity.

If you are interested in housing the Kaiser’s mountain newt in your own collection, specimens can sometimes be found for sale, but be careful to determine that the newts you’re considering have been captive bred, because wild newts are still being collected from the wild.

Emma Lawlor, Cat Chew and Gary Miller are animal technicians at Sparsholt’s Animal Management Centre. Emma previously was involved in a conservation survey for South American snakes, notably the Hog Island boa, and Gary previously worked in conservation of wild crocodiles in Africa.

James Brereton is a lecturer in Zoo Biology at University Centre Sparsholt in Hampshire, England. Previously, he developed his experience with reptiles and amphibians through work at ZSL London Zoo and Beale Wildlife Park. He may be contacted at James.Brereton@sparsholt.ac.uk.

Further Reading

Farasat, H. and Sharifi, M. (2016). “Ageing and growth of the endangered Kaiser’s mountain newt, Neurergus kaiseri (Caudata: Salamandridae), in the Southern Zagros range, Iran.” Journal of Herpetology.

Mobaraki, A., Mohsen, A., Alvandi, R., Tehrani, M. E., Kia, H. Z., Khoshnamvand, A., Forozanfar, A. B. E. and Browne, R. K. (2013). “A conservation reassessment of the Critically Endangered, Lorestan newt Neurergus kaiseri (Schmidt 1952) in Iran.” Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, 9(1), 16-25.